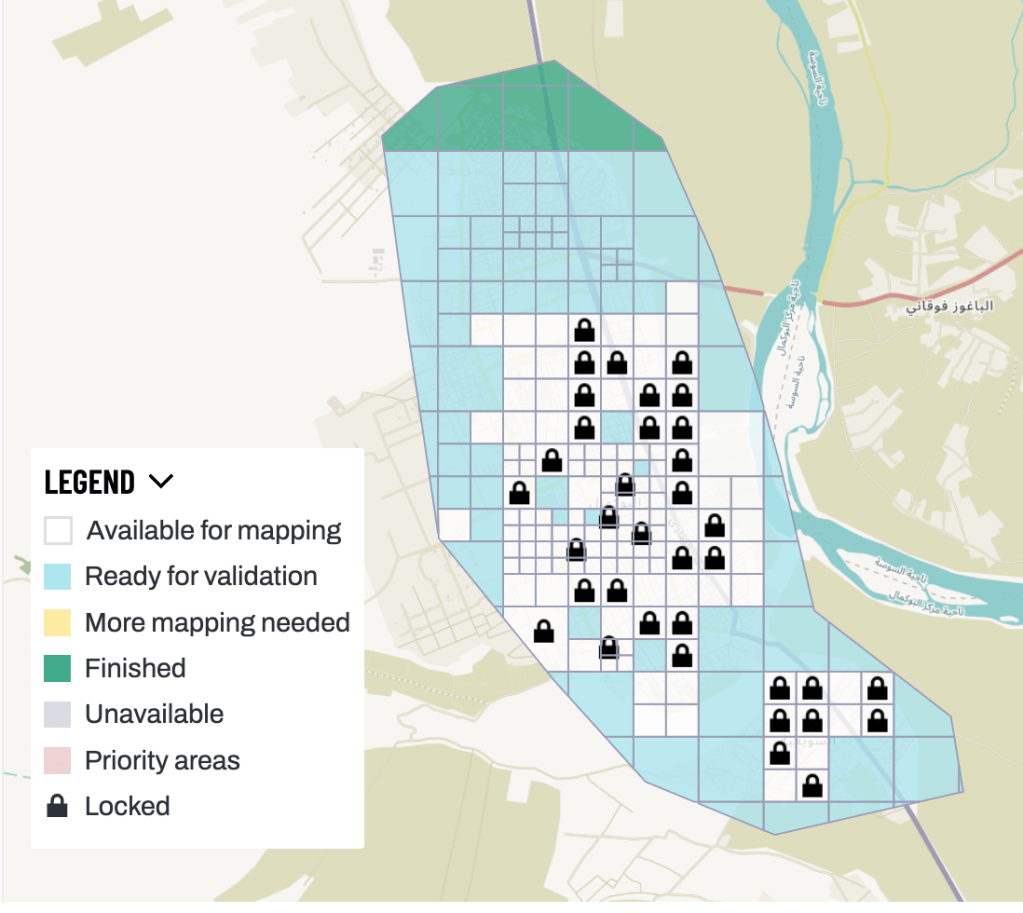

Fourth quarterly participation

- Location : Syria

- Project Number : Project #28749

In Syria, the economic crisis has compounded the humanitarian crisis caused by the war, with greater numbers of people than ever in desperate need of assistance.

Why are they there?

based on information in https://www.msf.org/syria

We see people in the camps suffering from poor living conditions and an overall lack of humanitarian assistance, mental health support or access to vaccinations. Supporting hospitals, basic healthcare centres and mobile clinics in displacement camps are also a central part of our response. Due to the poor living conditions in the region, injuries from domestic accidents are also frequent. We run a specialised surgical burns unit in northwest Syria to respond to such injuries.

What used to be a functional health system in Syria has been devastated by the conflict. Hundreds of medical facilities have been bombed, medical staff have been killed, detained or have fled, and supplies are lacking. Syrian health staff have been forced to improvise operating theatres and work in deplorable conditions, overwhelmed by emergencies. Over the past decade, we have not only dealt with mass casualties and acute emergencies but also the resurgence of preventable diseases.

As the conflict escalated in the early years of the Syrian war, so did the crackdown on medical assistance for people in areas that were not under the control of the Syrian Government. In areas we can’t access, we have tried to maintain a system of distance support to medical facilities and networks of medics. Over the years, we supported underground medical networks.

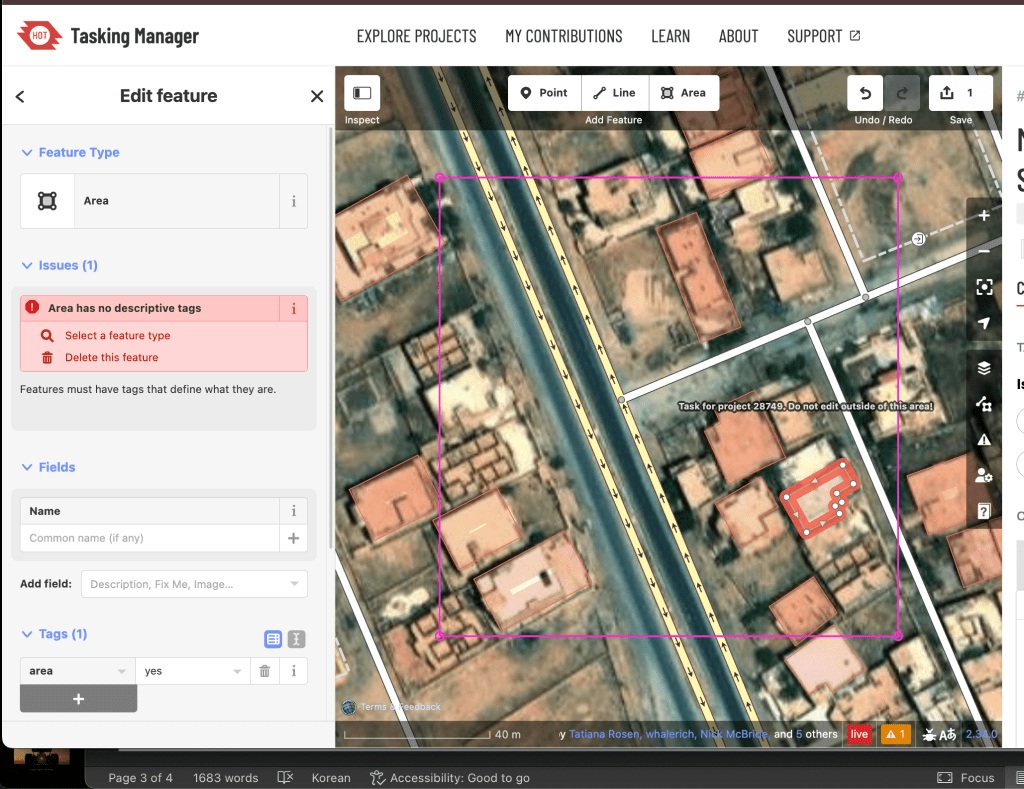

What I have found in Missing Maps

It is extremely hard to figure out whether it is a building or not based on a two-dimensional map, as everything looks the same. This is particularly challenging because the social fabric has been disrupted. We are not able to determine whether it is a school or hospital without social context. For example, when there is a large space of ground in front of a single building, we might judge it as a school. However, it could be a police station with a large courtyard. We can only figure it out when we actually get there, looking around and understanding what people are talking about.

That is, Satellite imagery often creates identical visual signatures for completely different building types. Again, A rectangular building with a courtyard could be a school, hospital, police station, military facility, or even a residential compound. The physical form doesn’t reveal the function.

While experienced mappers in Doctors without borders do learn to use contextual hints (building size, parking areas, relationship to roads, surrounding structures), these are often unreliable assumptions.

The Ground Truth Gap

Satellite and aerial imagery can tell us what is there physically, but not how it’s being used. This becomes especially problematic in crisis mapping where:

- Building functions may have changed due to conflict

- Temporary uses might not match original purposes

- Local knowledge is essential but often inaccessible

Too many resources and efforts

In the sterile glow of computer screens, sixty volunteers across ten teams spend hours tracing building outlines on satellite images of Syria. They zoom in on pixelated rooftops, carefully connecting dots to map structures that may house families, serve as schools, or provide medical care. Yet as one mapping session coordinator recently observed, “The artifacts we have made was limited. As maps is changing very fast… some contour of building they worked on will be destroying tomorrow in Syria. Then, what’s the point?”

This question strikes at the heart of a profound tension within humanitarian technology efforts: the gap between digital good intentions and ground-level impact.

The Limits of Digital Compassion: Lessons from Crisis Mapping in Syria

In the sterile glow of computer screens, sixty volunteers across ten teams spend countless hours tracing building outlines on satellite images of Syria. They zoom in on pixelated rooftops, carefully connecting dots to map structures that may house families, serve as schools, or provide medical care. Yet as one mapping session coordinator recently observed, “The artifacts we have made was limited. As maps is changing very fast… some contour of building they worked on will be destroying tomorrow in Syria. Then, what’s the point?”

This question strikes at the heart of a profound tension within humanitarian technology efforts: the gap between digital good intentions and ground-level impact.

The Paradox of Remote Humanitarian Work

Crisis mapping emerged from a compelling premise—that volunteers anywhere in the world could contribute to disaster response and humanitarian efforts through digital mapping. The 2010 Haiti earthquake demonstrated the potential power of crowdsourced mapping, where thousands of volunteers helped create detailed maps that aided relief efforts. Since then, the Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team and similar organizations have mobilized volunteers for crises from typhoons in the Philippines to conflicts in Syria.

Yet the Syrian mapping experience reveals uncomfortable truths about the limits of remote humanitarian intervention. Despite the dedication of ten teams comprising sixty volunteers, the tangible outcomes remain frustratingly modest. Buildings painstakingly mapped today may be reduced to rubble tomorrow. The very conflict that creates the humanitarian need also renders the digital response ephemeral.

This creates what might be called the “resource-impact paradox”—significant human effort producing limited lasting value. When volunteers invest hundreds of collective hours in mapping work that conflict may erase overnight, we must confront difficult questions about efficiency, sustainability, and the true nature of humanitarian impact.

The Fundamental Problem of Context

Beyond the temporal challenge lies a more intractable issue: the impossibility of determining function from form through satellite imagery alone. A rectangular building with an adjacent open space could be a school with a playground, a hospital with parking, a police station with a training ground, or a residential compound with a courtyard. The physical structure reveals nothing about its social function.

This limitation isn’t merely technical—it’s epistemological. No amount of improved satellite resolution or artificial intelligence can bridge the gap between what buildings look like and what they actually do. As one mapper noted, “You can figure it out when you actually get there looking around and translating what people talks.” The essential information exists only in the social context that satellite imagery fundamentally cannot capture.

Traditional mapping guidelines attempt to work around this limitation by teaching volunteers to look for contextual clues. Large open spaces might indicate schools. Clusters of small buildings could suggest residential areas. But these are educated guesses at best, and often wrong. The assumption that form follows function—already questionable in peacetime—becomes even more unreliable in conflict zones where buildings frequently change purpose out of necessity.

Beyond Compassionate Impulses

The coordinator’s observation that “what you can rely on is not the mere compassion but the strong solutions to work on” cuts to the core of humanitarian technology’s identity crisis. The field has long been driven by compassionate impulses—the desire to “do something” in the face of distant suffering. But compassion, while necessary, proves insufficient when confronted with complex technical and logistical challenges.

This isn’t to dismiss the value of compassionate motivation. The volunteers spending their evenings and weekends mapping Syrian buildings are driven by genuine concern for human welfare. Their dedication is admirable and necessary. But dedication alone cannot overcome the fundamental limitations of remote crisis mapping: the ephemeral nature of conflict-affected infrastructure, the impossibility of determining social function from satellite imagery, and the complex coordination challenges of managing distributed volunteer efforts.

The gap between compassionate intention and effective action becomes a source of frustration for both volunteers and the communities they seek to help. Volunteers may experience burnout when their efforts feel futile. Meanwhile, communities in crisis may receive assistance based on incomplete or outdated information, potentially misdirecting resources when every decision carries life-or-death consequences.

Searching for Solutions

Acknowledging these limitations doesn’t require abandoning humanitarian mapping entirely, but it does demand a more honest reckoning with what such efforts can and cannot achieve. Some projects have begun experimenting with hybrid approaches that combine remote mapping with local knowledge networks. Others focus on infrastructure types that are more easily identifiable from satellite imagery—roads, bridges, and hospitals with distinctive architectural features.

Real-time communication platforms offer another avenue for bridging the context gap. Mobile messaging apps can potentially connect remote mappers with local residents who can provide crucial social context about building functions and current conditions. However, these approaches face their own challenges: language barriers, security concerns, and the difficulty of maintaining communication networks in active conflict zones.

The most promising direction may involve fundamentally reframing expectations. Rather than attempting to create comprehensive, up-to-date maps of conflict zones, humanitarian mapping might focus on providing rapid damage assessments, identifying major infrastructure changes, or creating baseline datasets that local organizations can build upon when conditions allow.

The Search Continues

The Syrian mapping coordinator’s honest admission—”I can not find an answer till now. However, we’ll figure it out soon”—reflects both the frustration and persistence that characterizes much humanitarian technology work. This combination of acknowledged uncertainty with continued determination may be the field’s greatest strength.

The challenges of humanitarian mapping mirror broader questions about the role of technology in addressing global inequities. How do we bridge the gap between digital capabilities and ground-level needs? When does remote assistance become a substitute for more direct forms of engagement? How do we measure impact when the problems we’re trying to solve are constantly evolving?

These questions don’t have simple answers, but asking them seriously represents progress. The humanitarian technology field has sometimes suffered from technological solutionism—the belief that digital tools can solve complex social problems if only we build the right applications. The Syrian mapping experience suggests a different approach: one that begins with humble acknowledgment of limitations and proceeds with careful attention to what technology can and cannot accomplish.

Conclusion

The story of Syrian crisis mapping is ultimately about the collision between digital optimism and complex reality. Sixty volunteers, armed with good intentions and mapping software, encounter the fundamental limitations of remote humanitarian intervention. Their buildings disappear in airstrikes. Their functional classifications prove wrong. Their careful coordination struggles against the chaos of conflict.

Yet their work continues, driven not by naive faith in technological solutions but by a more nuanced understanding of their role in a larger ecosystem of humanitarian response. They map not because satellites can see everything, but because partial information is sometimes better than none. They coordinate not because remote volunteers can solve Syria’s crisis, but because distributed effort can support those who are closer to the problems.

The question “what’s the point?” doesn’t have a simple answer. But perhaps the point lies not in the perfection of the maps themselves, but in the process of grappling seriously with the challenges of connecting across distances, of translating compassion into effective action, and of maintaining hope while acknowledging limitations. In that ongoing struggle, even imperfect maps become acts of solidarity—imperfect, temporary, but genuine attempts to bridge the vast distances between those who suffer and those who seek to help.

The social context challenge remains unsolved, but the search for solutions continues. And perhaps that search itself—honest, persistent, and humble—represents the true value of humanitarian mapping efforts: not as a complete solution to human suffering, but as one thread in the complex tapestry of human connection across conflict and distance.

Why are they there?

based on information in https://www.msf.org/syria

We see people in the camps suffering from poor living conditions and an overall lack of humanitarian assistance, mental health support or access to vaccinations. Supporting hospitals, basic healthcare centres and mobile clinics in displacement camps are also a central part of our response. Due to the poor living conditions in the region, injuries from domestic accidents are also frequent. We run a specialised surgical burns unit in northwest Syria to respond to such injuries.

What used to be a functional health system in Syria has been devastated by the conflict. Hundreds of medical facilities have been bombed, medical staff have been killed, detained or have fled, and supplies are lacking. Syrian health staff have been forced to improvise operating theatres and work in deplorable conditions, overwhelmed by emergencies. Over the past decade, we have not only dealt with mass casualties and acute emergencies but also the resurgence of preventable diseases.

As the conflict escalated in the early years of the Syrian war, so did the crackdown on medical assistance for people in areas that were not under the control of the Syrian Government. In areas we can’t access, we have tried to maintain a system of distance support to medical facilities and networks of medics. Over the years, we supported underground medical networks.

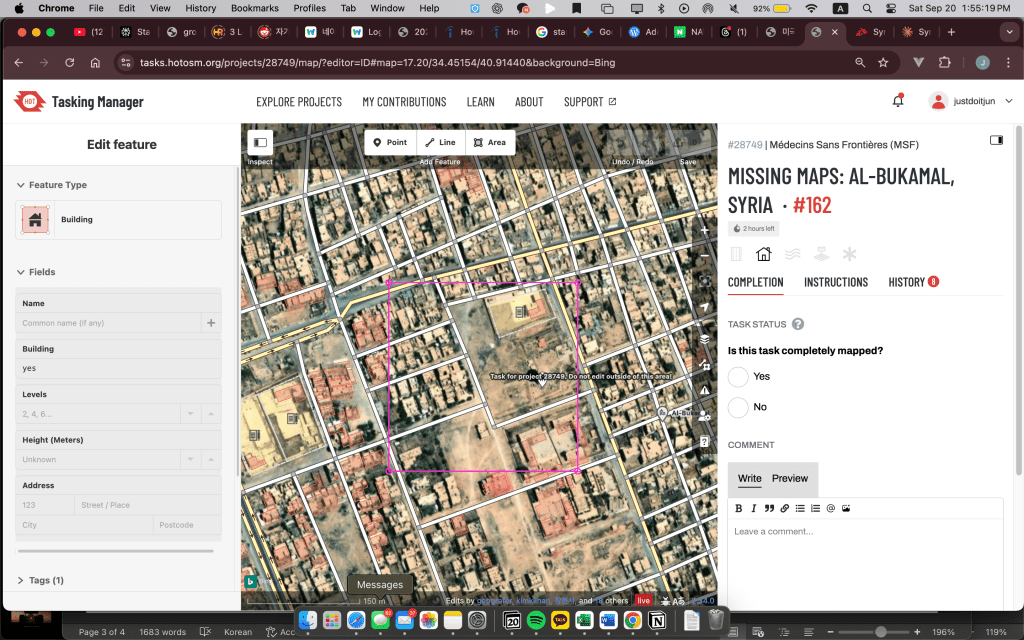

Building Mapping Guidelines for Syria

Destroyed Buildings

Syria frequently has buildings that have disappeared due to civil war. There may be mapped buildings that are not visible in photos. However, don’t immediately delete buildings – press Ctrl+Shift+H to check the building’s history.

Decision Process:

- Building mapped before February 2023 → Now missing building → Delete

- Building mapped after February 2023 → Should be visible on map but not showing → Leave it alone

- Difficult to determine → Leave it alone

Hish-rise Building Mappings

High-rise Building Mapping: Map the building footprint where walls meet the ground, not the roof outline. If you’re accustomed to connecting visible building corners from photos, this might actually be more difficult. Therefore, you need to map the building’s footprint area.

Small tips while building maps

I should have saved artifacts when I have about 5-10 edits. If too many edits are saved at once, errors occur.

Record

Leave a comment